When Abylight started working in Cursed Castilla (Maldita Castilla EX), the Nintendo handheld console was, without a doubt, the platform where we wanted the game to be played.

It was obvious that a game created with such care would be a perfect fit for the Nintendo 3DS. On the other hand, accomplishing it would not be exactly straightforward.

Cursed Castilla was developed with GameMaker, an ideal tool for creating 2D games that supports mobile, PC, Xbox One and PS4. Sadly, GameMaker does not support 3DS and – at the point in the lifetime of the console – we do not think it will ever do.

Even so, we decided that we really wanted to launch the game on 3DS, no matter what. And to achieve that heroic deed, we had only two possible paths…

Should we make a ‘port’ or a ‘remake’?

The game is developed in GML, the programming language used in GameMaker. Since the original source code of this engine is not available, we considered creating a remake of the game: extracting the graphs, sounds and maps from the project, and programming again the whole game for the Nintendo handheld.

Although it seemed easier at first thought, a detailed study of the game code revealed that, years of work polishing again and again the gameplay meant that every pixel of Cursed Castilla was placed with millimetric accuracy.

So, trying to reproduce faithfully from scratch the level of polish achieved in the original game would be incredibly complex. We would have to invest a lot of resources re-doing a game that it was already great, instead of concentrating in the challenge of the adaptation itself.

How to develop a GameMaker-compatible engine?

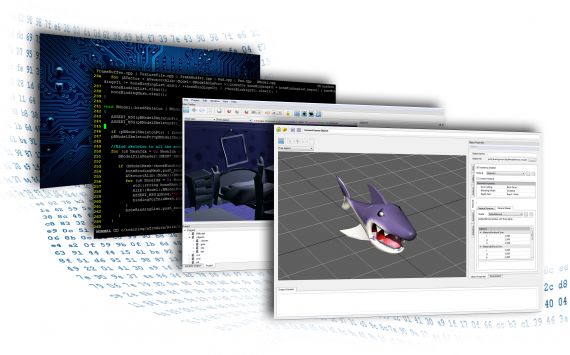

The second option was tackling the problem at its root and developing an engine compatible with GameMaker for Nintendo 3DS, so we would be able to use the original source code of Cursed Castilla.

The first step was to determine how to extract the GML code and the rest of the information from GameMaker in order to create the compatible engine.

There were three options for that: we could try to interpret directly the GameMaker bytecode (the intermediate code, which is more abstract than the machine code, which usually is a binary archive). We could also compile the GML language ourselves, or use the C++ code generated by GameMaker in the native export of the YoYo compiler.

The bytecode option was discarded after a quick analysis. Despite being great for PC development, it is impossible for a Nintendo 3DS to interpret it with reasonable speed.

Creating our own GML compiler was also discarded. We can promise that should we had reverse-engineered the GameMaker functionality and programmed our own compiler at the same time, Cursed Castilla for 3DS would be still in development!

Thus, there was but one option: using the C++ Code generated by GameMaker when exporting in native mode. At that time, we didn’t know exactly how efficient this ported C++ code would be, but at least it was a starting point.

So, we started from that code and linked it to our own compatible API. The rest of the graphics, the sounds, path and other elements were easy to obtain from the GameMaker data files.

Organizing the work

On the one hand, this version of Cursed Castilla required developing an engine compatible with GameMaker; on the other hand, we had to adjust every detail of the game, and there were quite a few: deciding what to do with the bottom screen, reorganizing the maps to get the astounding 3D stereoscopic effect, creating player profiles…

Fortunately, Abylight Studios had spent years investing and developing our own engine, VEGA, which is multi-platform and 100% modular. The great advantage of having our own engine is that we could do almost anything with it in order to adapt it to the requirements of the project.

How to develop for Nintendo 3DS using GameMaker with no actual support to do it

Although Vega is a 3D engine, the 3D module can be removed without any problems. In its place, we developed a new module: our own implementation of the GameMaker API.

VEGA also has a hardware emulation layer that allows us to have the look and feel of other machines, even if it is native code. Through this approach, we started to develop the port in Linux, but with a version virtually identical to a Nintendo 3DS — all before we started to compile everything in the Nintendo handheld. Thanks to not having any speed or memory constraints, we were able to fix bugs and polish the game on a PC.

One important detail: developing the VEGA extensions necessary to make it compatible with GameMaker and capable of supporting Cursed Castilla would take some time. While we were developing the engine, we could not implement any of the specific features of the 3DS version that the game needed– so we had to parallelize the work to avoid the porting process to last forever.

New features

Since our goal was to release a great Nintendo 3DS game (for God and Castilla!), we had to squeeze the 3D features of the machine to their very limit.

We worked in all the elements of the game to get a flawless “feeling” of depth. The main elements of the game, such as the enemies, the projectiles, the platforms or Don Ramiro himself, all of them are in the forefront, while the secondary elements are in a further plane. This creates a much more immersive experience and allows the player to focus on the hazards of the game.

Then, there was the issue of the bottom screen. With a game like Cursed Castilla, created with a single screen in mind and with all of its elements placed with care and precision, reallocating some secondary elements of the UI such as meters, markers or maps on the bottom screen was deemed a solution as easy as lazy — one that Cursed Castilla did not deserve. So, we asked ourselves: what can we do with the bottom screen?

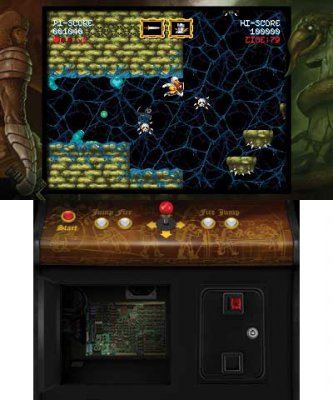

Locomalito conceived Cursed Castilla as homage to the arcades from the late 80s and early 90s. It was drawn with the same palettes and number of colors — even the music was created with the sound chips those machines used! For us, keeping that spirit was extremely important.

Then an idea came to us: what if we go for a total homage to that era with a full-body arcade machine? Following the philosophy we applied in previous projects as the Music On series for Nintendo DS, we transformed the console into something as similar to an arcade machine as we could.

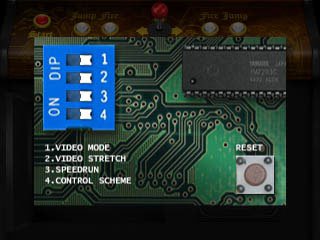

The arcade machine controllers are 100 % functional: they react to the input of the tactile screen and the console buttons. You can open the service door and extract the arcade board to play around with its configuration, changing the screen size, adding the speed-run counter or remapping the controls. We even placed a small Easter egg: the coins placed in the control panel can be introduced in the slot creating a surprise effect (but, sssh, don’t tell anyone about it, it’s a secret!).

Everything was created with the maximum level of detail: even the sound effects have been recorded from a real arcade machine!

Ending: A blessing, not a cursed experience

To put it in a nutshell: developing the 3DS version of Cursed Castilla has been a long journey with quite a few efforts and struggles. However, seeing how happy the players are with the game is super rewarding for the team, and that’s worth every single effort.

Thanks to our accumulated experience, combined with our seniority as developers for Nintendo handheld platforms, we are able to port games designed originally for more powerful platforms (e.g. a PC) for something smaller as a Nintendo 3DS. As it were, we can put a whole ocean into an aquarium!